I’ve provided various advice to Passive House designers and clients about what to specify and how to locate heat pump hot water heaters. But until I read a post by one of my building science heroes, Joe Lstiburek, I had not thought about the issue of cold exhaust air. There are places you don’t want that exhaust pointing. If cold air hits a surface, especially in a humid environment, it can cool it down below the dew point. And guess what loves cold surfaces with moisture? Yes, mould.

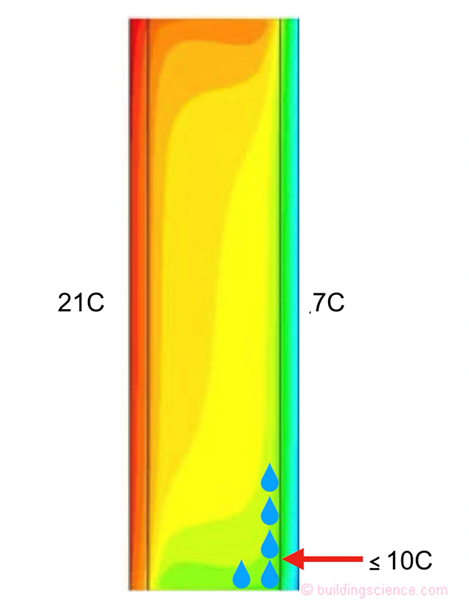

“Close up of the interstitial space in the wall. Notice the temperature gradients within the wall. Moisture will condense on surfaces below the dew point, this time hidden within the wall cavity. What if this was an external wall with insulation and some outdoor summer air leakage into the wall cavity?” From Joe Lstiburek’s post, here. Units changed to Celsius.

Joe’s article has plenty to say about sticking the units in cupboards, which is the American approach (and where New Zealanders traditionally put their hot water cylinders—inside the home). A constantly cooled confined space is going to get problematic fast, so their advice is to locate the unit in a room with at least 12m2 of floor area. North American basements are ideal; here it’s more likely an attached garage. The other option is to fit a louvred door on the cupboard but the fan creates noise and this will generally be unwelcome in living areas. (Check out Joe’s post if you want to see some photos of problematic installs in the American context.)

Where to put a heat pump hot water heater

Outdoors

My first advice is always to locate the unit outside where there’s plenty of air circulating. Ensure suitable protection from the elements and that the unit’s airflow is not blocked.

Outside install example, using a poured concrete slab with steel bracing. Located under an eave with additional weather protection from a retaining wall.

Unconditioned space

Putting the unit in an attached garage is another possibility but make sure:

- you’ve minimised the pipe run in the plumbing plan

- you specify appropriate levels of insulation to pipes and connections and ensure the plumber fits this (why does the typical New Zealand plumber loathe insulating pipes?)

- provided enough airflow

- ensured the cold exhaust isn’t aimed directly at sensitive materials like paper-faced gypsum wallboard.

Split system

A third option is a split system, with the noisy fan outside and the cylinder inside. This avoids the problem of cold exhaust air hitting vulnerable surfaces but this style of unit can be 50% more expensive than the all-in-one option and adds complexity to the project too. It does allow for using heat pumps that have CO2 as the refrigerant (for the least GHG impact). There are specific use cases where split systems are the best option but understand the pros and cons.

Ducted outdoor air in and out

I was frankly astonished when I first saw plans for New Zealand Passive House projects where the all-in-one unit is inside the thermal envelope and inlet and exhaust air is ducted. It seemed crazy, but it’s been done at least twice and seems to have worked out well. It certainly avoids the issues described above.

Final considerations

Remember though that unless it’s ducted, having a heat pump compressor inside the home will impact on heating demand in winter. While it’s heating water, it’s cooling the surrounding area. The space heating system will need to work a little harder to compensate. In summer however, it will assist a little with cooling.

Lastly keep in mind the opportunity cost of siting the heat pump hot water heater inside. It’s taking up a metre of floor space that almost certainly cost $5-8K to build. Particularly on a small project where every bit of space counts, there are almost certainly better uses for that one square metre. Lastly, wherever that unit goes, it is heavy! Consider what it sits on and specify suitable earthquake restraints.