The energy savings offered by building to the Passive House standard are easy to quantify. The comfort and healthiness of these homes is very much felt by those living in them but quantifying these benefits that come from living in a warm, dry, properly ventilated home has been difficult.

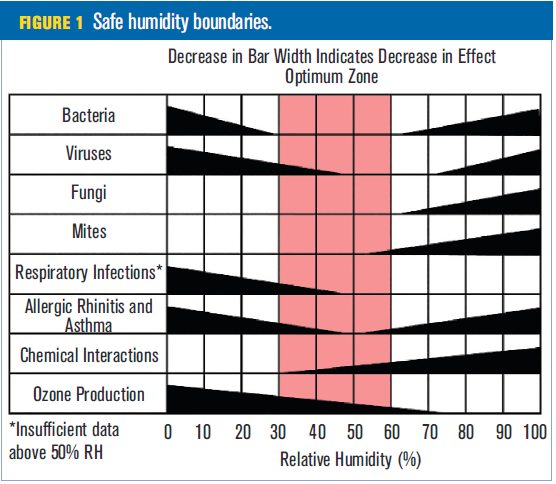

However, a recent article in ASHRAE Journal takes us forward in quantifying the health value of good indoor air quality. The article by Peter Luttik points to a growing body of research showing that keeping indoor relative humidity in the sweet spot of 40-60% drastically reduces the viability of bacteria, viruses, fungi and mites. This I knew.

Figure from Luttik, P. (2025, July). Beyond DOAS. ASHRAE Journal, 18-22.

But his attempt to quantify this using a metric called Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) is new to me. A DALY is a measure of overall disease burden, representing the loss of the equivalent of one year of full health. Research indicates that typical indoor air quality can cause a loss of 0.22 DALYs per occupant per year, which is a shocking figure. The good news is that by actively managing indoor air quality—controlling humidity, filtering air, and ensuring proper ventilation—this risk can be slashed by two-thirds, down to just 0.06 DALYs per person.

So, what’s that worth in dollars? If you value one DALY at the minimum of the equivalent of a year’s income (as is typically done), the health benefit of breathing clean, healthy air at home is enormous. Even using a conservative number, that could easily be a benefit of over $10,000 per person, every single year. Suddenly the investment in a high-performance home doesn’t seem like a cost, but a ridiculously good investment in people’s long-term health.

It’s great to have engineers providing the data to back up what we know experientially: Passive House provides massive, quantifiable health benefits that can improve, and even extend, the lives of the people inside those buildings.

Passive House projects deliver these outcomes by design

Humidity Control: The constant, low-level ventilation from the MVHR system should keep the relative humidity in a certified Passive House building within that healthy 40-60% RH range.

Filtration: The article identifies fine dust (PM2.5) as the single biggest health risk, with particles in the range of PM2.5 to PM10 causing 84% of the harm in terms of DALYs. Standard practice for Passive House MVHR systems is to use F7 filters (equivalent to MERV 13), which capture 65-80% of these particles. This is the level of capture assumed in the article’s calculations.

Fresh Air: Continuous ventilation also dilutes other indoor pollutants like VOCs and formaldehyde, which the study also flags as contributing to the indoor air quality risks.

Note that the article focuses on Dedicated Outdoor Air Systems (DOAS), which are basically equivalent to the MVHR (Mechanical Ventilation with Heat Recovery) systems used in New Zealand Passive House projects. The one difference is that DOAS were originally developed for hot and humid climates, where preventing mould is important. These systems often have an added emphasis on active humidity control, not an issue in most New Zealand climates.

Abstract

The article “Beyond DOAS” by Peter Luttik discusses the evolution of Dedicated Outdoor Air Systems from their original purpose of humidity control in hot climates to a new focus on decarbonization and health. It highlights how modern systems can create significant value by improving indoor air quality, which can be quantified using metrics like Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs). The author argues that investing in smarter systems that provide demand-controlled ventilation, advanced filtration, and humidity control can deliver substantial health benefits, improve productivity, and reduce absenteeism, potentially offering a return on investment that far exceeds energy savings alone.

Reference

Luttik, P. (2025, July). Beyond DOAS. ASHRAE Journal, 18-22.

(This article is not published online.)

Comments 1

The foundational research by Morantes et al. (2024) establishes a total median harm from residential indoor air contaminants of 2200 DALYs per 100,000 person-years, which normalizes to 0.022 DALYs per person per year. The figures presented in the ASHRAE Journal article appear to be overstated by an order of magnitude, a discrepancy most plausibly explained by a decimal point error during transcription. This error significantly inflates the perceived public health risk of typical IAQ, exaggerating its contribution to the total burden of disease from approximately 0.7% to 7%.

It’s still a huge number using $60,000 NZD for a lower estimate of the value of a DALY and 0.014 DALY saved per person per year means a house of 5 people receives a $4,200 NZD value per year from better IAQ!

Giobertti Morantes, Benjamin Jones, Constanza Molina, and Max H. Sherman, “Harm from Residential Indoor Air Contaminants,” Environmental Science & Technology 2024 58 (1), 242-257 DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.3c07374