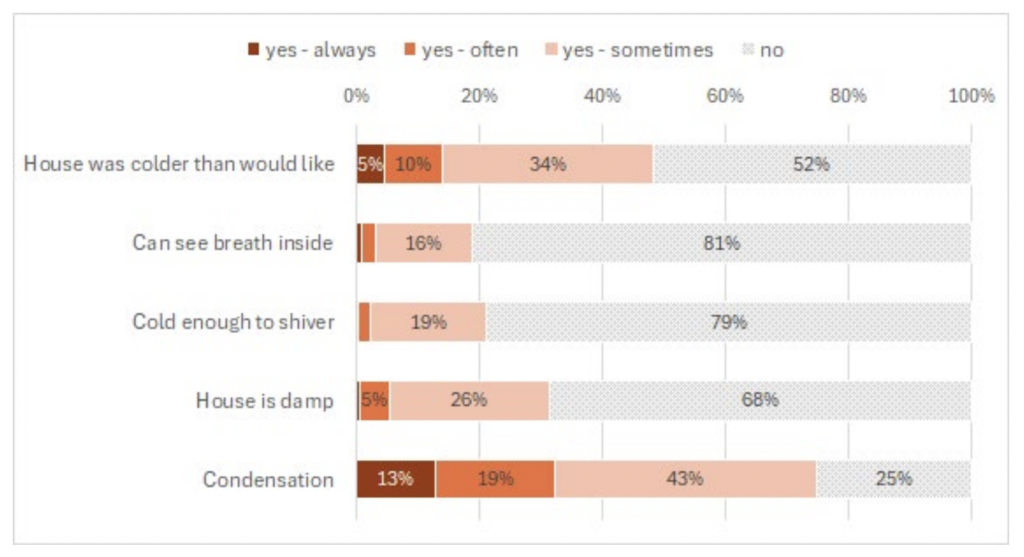

Figure 14. Comfort and problems in the home in winter – HEEP2 (Full + Medium). © BRANZ

New Zealand homes are slightly less cold in winter compared to 20 years ago. More New Zealanders appear to be heating at least some bedrooms, some of the time, to some extent. That’s the good news in the preliminary results from the HEEP2 study.

It’s faint good news, given other findings. About a fifth of those surveyed said they could see their breath inside and a similar amount said their home was cold enough that they shivered at least some of the time in winter. Nearly half of respondents reported visible mould in their home, with 11% saying the area of mould was larger than a sheet of A4 paper. A full third reported their home was damp at least some of the time.

These findings are from the Household Energy End-use Project 2 (HEEP2), a large national study of energy use and conditions in New Zealand homes conducted by BRANZ. Evening living room temperatures have risen from an average of 17.8°C to just under 20°C in 20 years, and average night-time bedroom temperatures have increased from 13.6°C to 16.1°C. This could reflect an increase in the number of bedrooms that are heated as well as increased levels of insulation. It’s still well below World Health Organisation guidelines, especially for the young, elderly or medically vulnerable.

Of course you have to dig into the data to identify what averages disguise. Unhealthy night-time bedroom temperatures are more common among lower-income households in the study: no surprise. Thankfully bedrooms for young children were more likely to be heated than other bedrooms, however around a third of respondents said their kids’ rooms were never heated. I feel for any parent forced to choose between paying rent, buying food and paying basic utility bills.

HEEP2 is collecting data from over 750 households across Aotearoa New Zealand. This includes a survey of 425 households, with 287 of these also being monitored for energy usage and indoor conditions. It’s the only national study of its kind for 20 years.

It is bizarre to me that despite all these findings, nine out of ten respondents consider their home is a healthy place to live. This even while many still experience cold, damp, condensation and mould, and wish their home was warmer. I understand there’s a generational shift among those who can afford to heat but there is still a strong cultural streak of stoicism*. Too many New Zealanders still normalise really cold housing. I’m grateful for the sustained, determined work of researchers like Phillipa Howden-Chapman who have created awareness that living in cold, damp homes is profoundly unhealthy, not just uncomfortable and unpleasant.

How to fix cold, damp housing

So from a building science point of view, what are the solutions? In order to dry out the moisture that is constantly created inside a home (by cooking, washing and simply breathing), occupants must heat and ventilate. This is even more important in temperate climates compared to cold climates. The outside air in winter in, say Bay of Plenty, contains more moisture than the colder air in Southland. That incoming air needs to be heated to reduce the relative humidity, so that the fresh (and now drier) air mixes with the stale, moist air which is then extracted. The end result is a drier home.

Sound inefficient? Yes it is, especially as most New Zealanders homes aren’t ventilated nearly enough to ensure healthy levels of CO2. Every new home being built should have at the very least a basic level of mechanical ventilation. These are feasible options available if you’re retrofitting or doing a renovation but they are much easier to install at the time of original construction.

The gold standard is mechanical ventilation systems with heat recovery (MVHR) in an airtight home. In winter, air (and warmth) isn’t leaking out through the cracks. Stale air is being constantly removed from damp rooms like the kitchen and bathroom, but its energy is used to pre-warm the filtered fresh air that is continually being brought in.

Without mechanical ventilation, people need to flush ventilate their homes by opening up all the windows for 20 minutes several times a day. Nobody wants to do this and almost no-one does, not when it’s barely warm enough inside and freezing cold outside.

Dehumidifiers for symptomatic relief

If all you can do is deal with symptoms, then I recommend you install a dehumidifier with a humidistat. Set it to 70% RH and run it all winter—for as much of the year as you are keeping windows closed and running the heater. There is some specific advice about how to set them up in this article. The electricity used to dehumidify will provide a bit more than 100% efficient heat to the home so there’s no additional cost in energy or money if you are using resistance electric heating.

Heat pumps of course are much more efficient than resistance heaters, costing much less to generate an equivalent amount of heat. And while the radiant heat from wood burners helpfully reduces RH, they also have negative effects on indoor air quality.

Reference

BRANZ SR495 HEEP2 report

*I’m so puzzled by this cultural trait that my first book considered it at some length. See the sidebar, “Why do we put up with it?” in Section I of Passive House for New Zealand: The warm healthy homes we need.