Like always, Otago University’s Public Health Summer School this month was galvanising. Creating better housing in order to produce a triple benefit—improved energy efficiency, reduced carbon emissions and better health—was the theme this year. The questions are huge, the stakes are critically high and the solutions are various but all complex.

I also watched a government official get blindsided by a question from the floor about how we report this country’s carbon impact. The conventional lens, that allows for comparisons between countries, is to report on CO2 production. New Zealand’s economy is quite unique for a developed nation because of the size of our primary sector and that its products are overwhelmingly exported. We generate CO2 from farming and from transport*. That’s incredibly disempowering and is leading to knock-down, drag-out fights between the rural sector and those pushing for climate change mitigation.

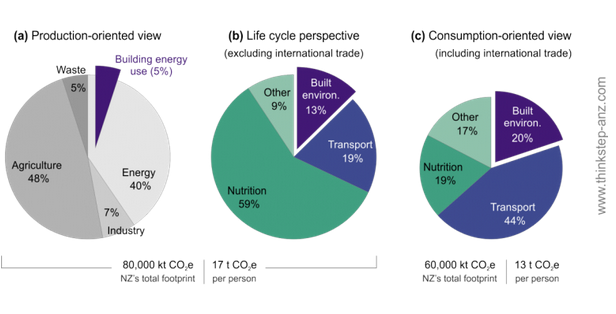

But what happens when we switch the lens through which we view the data? Looking at New Zealand’s carbon emissions from the point of view of consumption shows a very different story, as helpfully illustrated in this figure from the Thinkstep Report: The carbon footprint of New Zealand’s built environment.

Measured this way, our built environment contributes about 20% of our carbon impact. And I see a problem that we already have the tools to fix, unlike farmers who need cows that don’t belch methane. Just one example: build much more with local timber instead of steel and concrete. (Cross-laminated timber is a game-changer that makes very tall timber buildings possible but standard timber framing can still build five or six stories high.)

But we need structural shifts to make changes on the scale required. It can’t be left to the mythical free market and individuals because frankly, look at the mess market forces have got us into. We have some of the most unaffordable housing on the planet, we treat homes like a disposable consumer product and we optimise for the lowest first cost.

The current system fails to capture the value of building a better quality home. Valuers consider the size of the house, its location, its aesthetic. How many bedrooms and bathrooms, does it have a pool, a media room, how big is the garaging?

A certified Passive House has dramatically better quality components, its ongoing heating and cooling bills be will around 10% of a conventional, comparable, newly-built house and it is a much healthier environment to live in thanks to its building envelope and constant delivery of fresh filtered air via mechanical ventilation systems. For now, these benefits are not being accurately valued.

The whole industry is enslaved by a focus on the initial cost to build. If we are to solve the triple threat of unaffordable, unhealthy, carbon-hungry housing, we need to take a wider, longer-term view of the cost of housing. That needs structural change and it probably needs a stick as well as carrots.

An individual family looking to build a new home is pushed into building a bigger, more expensive home by their banker, their developer and their builder, all of whom make more money when housing footprints and first costs go up. It’s justified as an investment: it will be easier to sell and generate more profit when they sell, which we are told the average family does every seven years.

Choices that reduce that home’s embodied carbon and ongoing carbon emissions while also slashing running costs and increasing health and comfort of the occupants don’t look as attractive while the focus remains on the first cost of building rather than including the ongoing running costs. This is especially so when the housing market is speculative.

The family for whom the house was built may only enjoy the benefits of living in it for a few years, but that house is going to shelter other families for 50 or even 90 years and their health, and costs to heat and cool the house matter. So does the amount of carbon dioxide emitted every decade by that same building.

We have a huge task ahead to properly retrofit already existing housing stock. This makes it even more critical that the new houses being built now do not replicate the same errors (high energy use and carbon emissions, unhealthy, not durable), otherwise we lock in those problems for the next 50, 60 or even 100 years.

We must find ways to account for the value of cost-savings and benefits (both cash and social) against the initial costs to build. Sometimes there isn’t even a first cost to doing it better: a planned social housing project in Auckland could be built to Passive House standard at possibly lower first costs by making redundant the installation of hundreds of heat pumps. It will certainly slash running costs for the occupants and provide dramatic health benefits. The social costs of removing hundreds of vulnerable people from poor-quality, damp, mouldy, cold buildings and having them live somewhere dry and warm is huge. But those benefits and cost-savings don’t accrue to the same budget that pays the first costs of building and because of this, and nervousness about doing something new, the project may not proceed as originally planned.

New York City isn’t the first place most of us would think to look for solutions, but there is extraordinary work being done there to mitigate climate change, which threatens three trillion dollars worth of its coastal property.

John Mandyck from the Urban Green Council presented at the Summer School via video-link and there is a lot to learn from what this not-for-profit has accomplished. Its modes are four-fold: convene, research, advocate and educate, in order to accomplish its mission to “transform buildings for a sustainable future in NYC”. (More recently it has expanded that mission to “…and around the world”, as it realises its work can serve as a blueprint in other locations.)

The Council has developed consensus among broad and diverse stakeholders, made use of data and experts to drive decision-making, created ambitious solutions, focused on education and “making the technical relatable”.

In practice, it has shaped significant legislation, most notably the (state-level) Climate Mobilization [sic] Act. This introduced annual carbon caps per building that kick-in in just four years time and tighten in 2030. The caps vary by building occupancy type but the raw intensity metric doesn’t take into account the building density or intensity of use. It does create a trading market, allowing owners of energy-efficient buildings to sell their credits to buildings that are high carbon emitters.

There’s an interesting, readable summary of the Urban Green Council’s strategies here.

I’m about to help kick-off a project called ESCAPE that draws on this model with the goal of bringing about similarly radical improvements in building sustainability in New Zealand. Stay tuned.

*I’ve not gone into transport here, because it’s obvious we need to fix that and there are options available: electrifying transport and moving from road to rail are no-brainers, especially given this country’s relatively clean electricity generation.