Too many homes make people sick

The current talk about the housing crisis is almost entirely focused on affordability to purchase and homelessness. Yet there is a more pervasive problem, afflicting New Zealanders whether they rent or own. Researchers like Professor Philippa Howden-Chapman have been researching the health and social implications of sub-standard housing for years: there is a tonne of evidence.

New Zealand homes are too often cold, damp and hard to heat. More than three-quarters of current homes were built before 1978, the year the New Zealand Building Code changed to require minimal insulation. Even more recent homes built to the current Building Code can be uncomfortable and expensive to run.

New Zealand’s poor housing causes serious health problems, even early death. This country has

Let me count the ways:

Cold: The average New Zealand home is 16 degrees inside during winter, the temperature at which the risk of respiratory illness increases. At less than 12° C, there is a higher risk of strokes and heart attacks. World Health Organisation (WHO) guidelines call for an indoor temperature of at least 18–21° C if babies or elderly are resident.

Damp: Cold houses are usually damp houses; nearly a third of New Zealand homes are damp and rental properties are much more likely to feel damp than owner-occupied homes. Humans produce moisture through basic activities like cooking, bathing—and breathing. Moisture then condenses on cold surfaces. New Zealanders are all too familiar with heavy condensation on the inside of window frames and/or glass, that can run down the panes to pool on window sills.

“People do not find it strange to wear coats and outdoor clothing when indoors.”A Danish builder’s observation about New Zealanders.

One in six New Zealanders

Mouldy: A third of New Zealand homes contain mould. Not all mould is dangerous to healthy people but some are potentially toxic and spores can aggravate pre-existing respiratory conditions such as asthma. Some people have an allergic response to mould or are more susceptible to its health effects because their immune system is compromised.

Damp, cold and mould are a trio of problems that work together in a negative feedback loop: damp houses are very hard to heat and damp is a condition for mould to spread.

New Zealand homes are much damper (that is, they have higher relative humidity) than in many other parts of the world, because of our temperate climate and how we live in our homes. Modern construction materials and techniques are creating homes with less air leakage—almost by accident. Yet

The Building Code perpetuates this situation

The majority of homes are cold because they are expensive to heat due to firstly, design decisions driven by minimising capital costs and secondly, construction methods. That’s a failure of policy as well as the market.

If designers specify commonly used details, construction materials or types that have been designated as “acceptable solutions” in the Building Code, their designs will go through the Building Consent process quickly, down the “deemed to comply” route.

Doing better means not just spending more on components, but delays and additional costs in getting consents because it pushes consent applications down a so-called “alternative solution” pathway. For instance, architects specifying high-performance windows in bespoke homes complain about the additional hurdles they are asked to clear by risk-averse council staff. They may face requests for producer statements or other information, all of which costs them time and their

The Building Code fails because the minimum standards are too low and the industry regards them as a target to meet, not a legal minimum to exceed.

Asking whether architects and builders or their clients need to change their attitudes is a red herring. Fixing this problem requires

The current Building Code requirements for

Building costs are already high in New Zealand and a range of reasons are offered:

Building material costs alone are 20-30 % higher than in Australia. Housing and Urban Development Minister Phil Twyford pointed to an effective duopoly in suppliers in New Zealand and described the industry as rife with rorts and anti-competitive practices, sufficient for him to call for a market study investigation by the Commerce Commission.

If there are anti-competitive practices inflating building costs in this country, they need to be stamped out. New Zealanders deserve the best house they can buy for their money—paying for performance and durability, not for rebates and junkets designed to lock contractors into buying specific products.

Why do we put up with it?

Immigrants from Europe and other Western nations frequently ask why New Zealanders put up with being so cold, and living in homes that are damp and hard to heat. (A friend from Canada who settled in the Antipodes quipped, “When they told me it only got down to 16 degrees in winter, I didn’t realise they meant inside”.)

The roots of the cause may run deep in the Pākehā psyche. Ben Schrader, who has written histories about New Zealand housing and urban culture, points out that settler dwellings from the 1840s were predominantly constructed from timber and that British immigrants likely did not understand its much poorer thermal properties compared to the homes made of stone and brick that they had left behind.

Evidence from the time attests to early New Zealand cottages being under- heated and miserably cold. “It can only be surmised that a settler proclivity towards stoicism—discomfort was an attribute of colonial life—meant they have little thought to improving things,” Ben Schrader writes in his book The Big Smoke. “So it became a New Zealand custom to heat the kitchen, where the coal range was, and the sitting room, but not the other rooms.”

Historian Jock Phillips agrees: “Male frontier culture in New Zealand led to a denial of pain. To admit to coldness and discomfort was to reveal yourself as an effeminate urban weakling.” Perhaps those early settler experiences linger on, continuing to shape expectations and ideas about what is normal.

Builder Kim Feldman grew up and learned his trade in Denmark. Danish houses are warmed by central heating all winter because the outside temperature is constantly below zero—unlike his new home in Taupō which has milder winters with fluctuating temperatures.

He thinks there’s a lack of knowledge in New Zealand: “Many people are simply not aware that a poor indoor environment may have serious consequences for their health,” he says. There needs to be more education (He also notes, “People do not find it strange to wear coats and outdoor clothing when indoors.”)

He also points to economic drivers. “Many people look at their home as an investment—and in many cases a short term investment. They want their comes to be big, impressive looking and cheap. That way they can make more profit in the shortest possible time.

“A lot of the new buildings today could easily be 10-20 % smaller and still comfortably accommodate the people living in them. The capital saved could instead be used to improve the indoor climate, for example by building a Passive House or at least doing more than the Building Code specifies.

“I think that many people are simply not aware what it feels like to live in a

comfortable home, without mould on the window sills and a draught along the floor—or they think that such luxuries will cost them a fortune.”

Building Code climate zones are inadequate

New Zealand spans a wide latitude and people live at elevations from sea level to over 1130 metres above sea level. Our geography creates a wide range of climates but the Building Code specifies a mere three zones.

Using that scheme, a holiday home in the mountains in Queenstown is required to have no more insulation than a

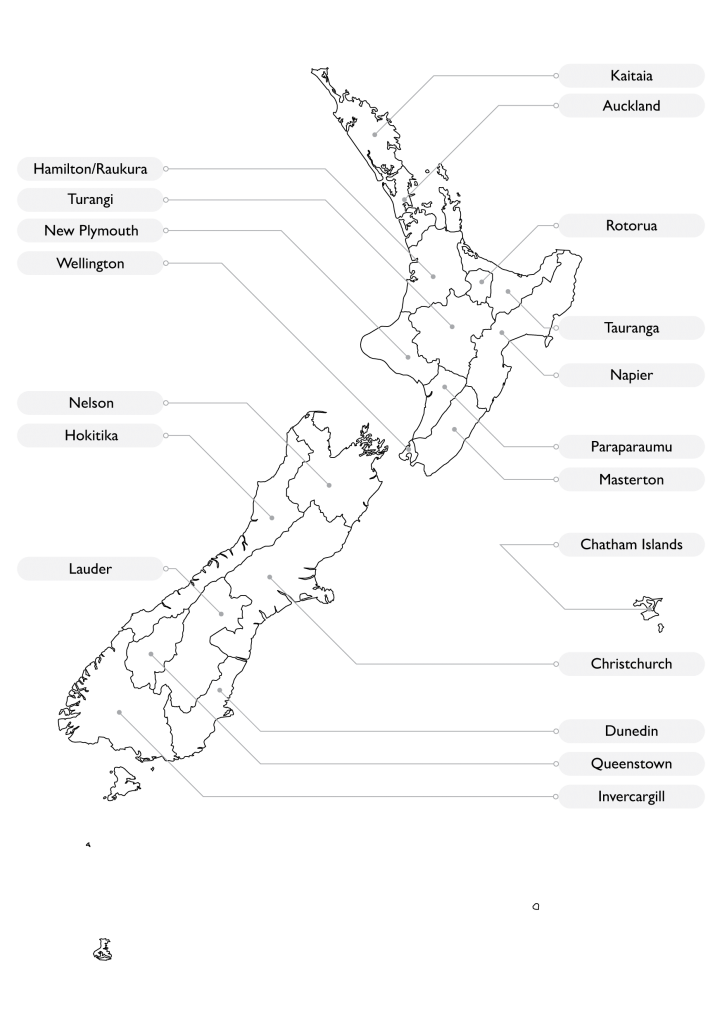

In contrast, 18 distinct climate zones were originally identified by NIWA. In a project undertaken by the author in 2015 and partially sponsored by PHINZ, 30 years of NIWA’s data from weather stations around the country was checked and its applicability for Certified Passive House calculations confirmed. Climate files are now certified for each zone, as shown in the map on page 6 even the Chatham Islands. This means anyone using PHPP energy modelling software (

One in six New Zealanders are sick with respiratory illnesses, which costs $6.16 billion a year in public and private costs.

There is no need for designers to guess, given the cost of getting it wrong is high. Underestimate and a building will need more energy to heat and/or cool. Overestimate and money is wasted on insulation beyond what is needed.

How we occupy homes is changing

We don’t build houses the way we used to. Materials have changed, and houses now contain

Construction techniques have also changed: pre-fabricated components and more streamlined workflows get houses to “lock-up” stage faster, giving rain- soaked timber framing less opportunity to dry.

Neither do we live in our houses the way we did 20 years ago. We actively ventilate far less: houses are typically tightly locked for eight or even 10 hours a day while occupants are at work and school. Windows may be closed overnight for security reasons.

For this reason, even modern homes that meet the legal minimum can be problematic. Take the case of a new home in Auckland with double- glazing and insulation: its owners are a professional couple who shower in the morning then head off to work, leaving the house locked up until the evening. The bathroom fan operates only while the shower is on. That’s insufficient to clear the steam, and the tightly shuttered house is damp and mouldy.

New Zealanders deserve the best house they can buy for their money—paying for performance and durability, not for rebates and junkets designed to lock contractors into buying specific products.

What hasn’t changed: families mindful of the cost of heating keep doors and windows tightly closed during colder months.

Yet the Building Code fails to address ventilation. As long as windows can be opened, the Code assumes they are being opened to provide adequate ventilation.

New Zealand’s Building Code urgently needs improvement to reflect the changes in building materials, construction materials and how people live in them; and to address the health problems created by our poor standards of building.

Inefficient buildings contribute to climate change

We need homes that are healthy for our people to live in. But we also need buildings that demand less from the planet.

New Zealand’s discussion about climate change mitigation is dominated by our agricultural emissions. It obscures an alarming fact: buildings use a huge amount of energy, about 40 % of the total primary energy consumption in developed countries. This is the sector with the greatest potential to reduce energy use and thereby mitigate climate change.

We can look overseas for examples of countries taking substantial action to meet carbon emission targets set under the Paris Agreement. Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Canada, among others, are seriously focused on reducing the energy consumption of residential and commercial buildings.

Take Vancouver, which has the greenest building code in North America. Since May 2017, the City requires all rezoning applications to meet low emissions building standards. This has seen a phenomenal increase in buildings that meet the Passive House standard.

Radical change is needed. Tinkering around with small upgrades may be worse than doing nothing. It risks creating what climate change scientist Diana .. Urge-Vorsatz calls “the lock-in effect”.

Consider a building owner who invests in an easy improvement like replacing old, poorly fitting wooden joinery with aluminium double-glazed windows. That’s better than before but falls far short of what is possible with thermally broken frames and double-glazing with low-E coating and argon fill. The cheap frames will conduct heat and collect condensation, leading to heat loss and moisture build-up—and very likely, mould. Yet the money already spent on new windows will create a significant obstacle to further upgrading them.

We can do better. We must do better.