2020 Jan 15 Update Link to webinar of the LCA tool – repeat of the PHI China conference presentation. Courtesy of PHI.

The objections to the Passive House concept are getting smarter*. The Passive House standard gives us the economically optimum level of thermal performance. In cold climates, we specify lots of insulation—WAY more than Code in most of New Zealand—because the cost of the insulation is far outweighed by the energy savings over the lifetime of the building.

But what about the whole life cycle environmental impact of all that additional insulation? Some critics argue that if we took into account all the environmental impacts of that extra material, we’d be better off in terms of CO2 emissions if we insulated less and used a bit more energy to keep interior temperatures comfortable. Especially, they say, given the proportion of NZ energy that is generated from renewable resources. I thought this argument might have some merit, but I haven’t had any data to check, until now. It turns out this argument is wrong—and not just a little bit wrong.

If you haven’t already, expect to meet clients who care about the materials used in their building from multiple standpoints: their family’s health, worker health and safety, fair trade, energy miles and (not least) global warming. What are the environmental impacts of extracting the base materials, transporting them, processing them—and at the end of their lifespan or usefulness, reusing or disposing of them?

Life cycle analysis (LCA) tools give us a way to quantify those variables and compare one product to another. BRANZ released version 3.3 of LCAQuick last month, a big improvement on the original tool. It’s designed to evaluate various environmental impacts associated with a specific building design. Now LCAQuick is a big Excel spreadsheet and so, of course, is PHPP. My engineer’s brain got to thinking about how to make them talk to each other so I could see the LCA impact of changing levels of thermal efficiency.

I’m currently in China, having just presented a paper (co-authored with BRANZ’s Brian Berg) about what I discovered when I got that integration working. The results surprised me, but it was a happy surprise. If you’re concerned about the amount of CO2 released over the lifetime of a building, Passive House levels of insulation are not excessive, even taking into account the extra materials needed to get to that level of energy efficiency.

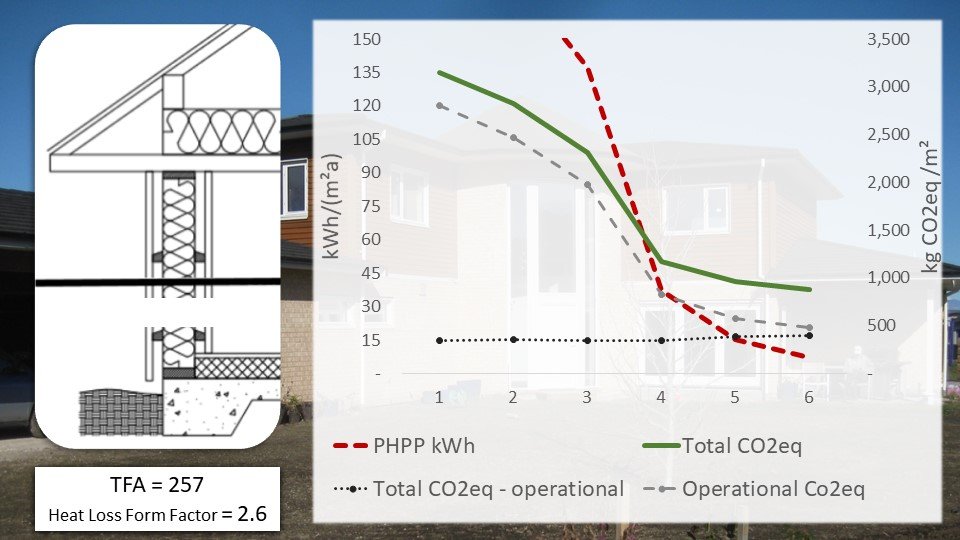

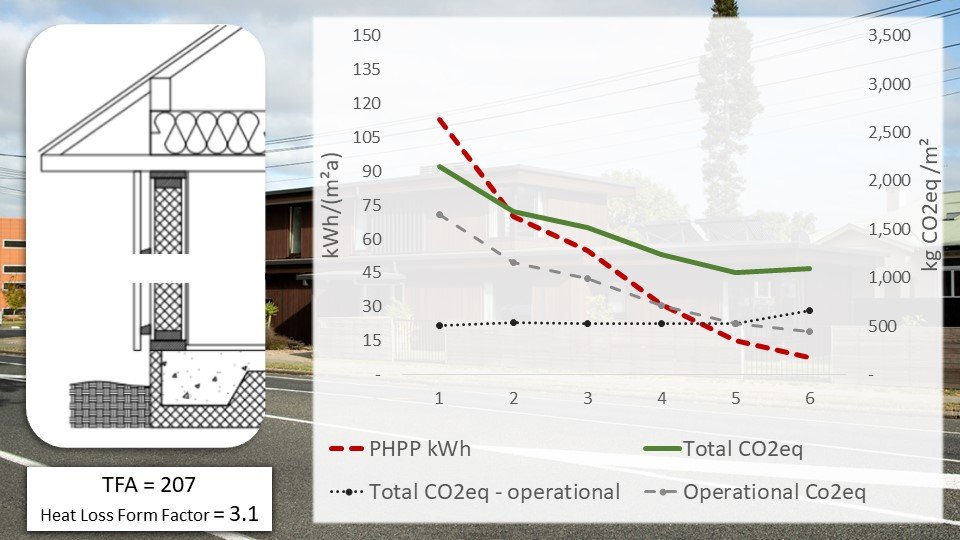

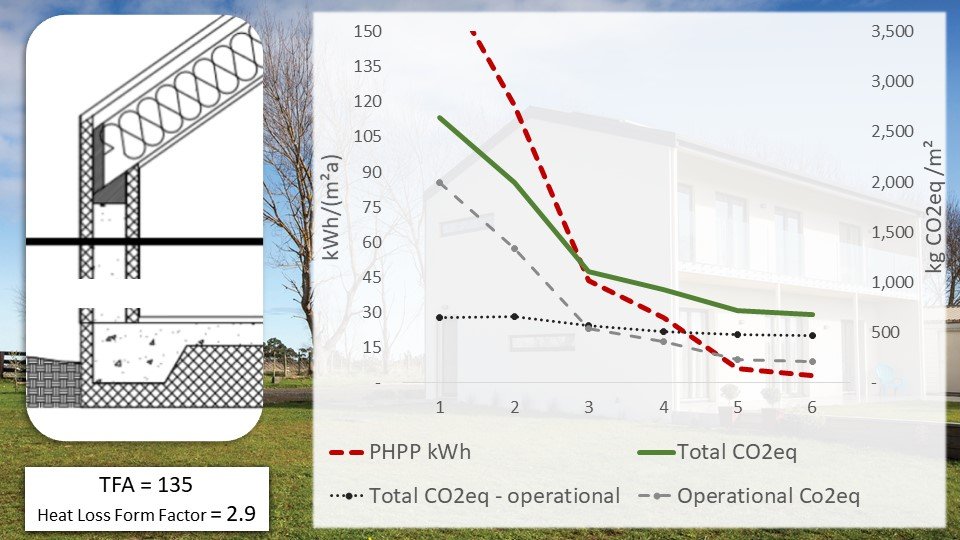

I modelled three different buildings that represent the most common construction methods now being used to create Passive Houses in New Zealand: modified timber frame, ICF and SIP.

For two of the three single-family homes assessed, the ecological optimum for energy efficiency was still not reached even at HALF the energy consumption of a certified Passive House. In other words, use even more insulation etc to make a PH twice as efficient, and you are still ahead on total CO2 emissions over the life of the building.

I also considered a SIP build in a warmer climate. The SIPs used XPS foam, which has more CO2 impact over its life cycle. Here the ecological and economic optimal points were very similar.

The technical paper I gave at 23rd International Passive House Conference can be downloaded here. That has all the geeky details, including more diagrams and numbers.

There is scope for more analysis. I only assessed the building materials that made up the building’s thermal envelope (ie not the internal fitout and building services, nor the material impacts relating to the MVHR system).

The LCAQuick tool can do more than measure contribution to global warming, which is what I focused on. It can measure, more or less roughly, a number of environmental indicators relevant to the initial design stage of buildings.

LCA data for NZ-specific materials and products is scarce unfortunately and any LCA tool is only as good as its database of materials. In the absence of published EPDs for example, generic data has been used by BRANZ. The material impacts in LCAQuick are for NZ materials, adjusted for material type and local travel distances. You can find a lot of background papers about its data, methods and validations on the BRANZ website (follow the link below).

The only other LCA tool with any kind of localised database for our small market is eTooILCD, which is both more comprehensive and more complicated.

One of the criticisms of PH levelled by Superhome proponents is that Passive House focuses only on a single criteria: energy efficiency. It’s not entirely true (because the comfort of occupants is also a certification target) but the criticism has some basis. Integrating LCAQuick and PHPP gives PH consultants another set of tools and measurements for designing buildings that are energy efficient, comfortable, healthy—and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

I hope more clients start demanding designs that deliver that; and that as an industry, we get smarter at explaining why it matters.

*Thankfully, we’re no longer hearing so much about how “Passive House is only relevant to cold European climates”, “passive solar is just as good” or dumbest of them all, “ewww, an air-tight box? That’s unhealthy”. I demolished these objections in my book, which you can download here (or email me if you want to buy a carton of real books to hand out to your clients, as a number of architectural practices and builders have done.)