Selecting windows for a Passive House isn’t easy, as I was reminded this week when talking to a friend about her new build. We’ve developed a standard set of questions we work through with Passive House designers and architects, part of our Detailed Design service. Here’s a quick (free) précis of what we encourage designers to consider.

First question: materials

There is now a wider range of materials available and some more affordable choices. If budget is tight, check whether your client will consider uPVC. Going up the price scale in order, there’s aluminium-clad uPVC, timber and timber with an aluminium exterior.

These uPVC windows were selected for this high-performance retrofit in Wellington for reasons of budget and low maintenance.

The climate and design will dictate whether a particular project needs double or triple-glazing, which may impact on the materials choice. Timber windows are expected to be more durable over time, but that’s not entirely certain and depends on maintenance.

Second question: origin

Do understand that all glazing is imported; there is no window glass made in New Zealand. However, some frames are made locally. The advantage is a shorter lead time, but your choices are limited. At time of writing, there are two timber window manufacturers that make Passive House-certified windows in New Zealand and a couple of others that produce high-performance windows that could be suitable.

Only a few uPVC window manufacturers in NZ can meet the minimum standard required for a Passive House build. At time of writing, none are certified. They may be suitable, depending upon your building design, but sourcing the data and checking takes time.

As an aside, don’t get yourself in a situation where windows have been ordered (or worse, installed) that don’t deliver the performance the project needs. Getting data out of component manufacturers is not always easy. This is why buying windows that have already been certified to Passive House standard is an easier, safer option.

If you are open to specifying imported components, then your choices expand (and the decision becomes harder). There is a range of importers working at different scales, from a part-time activity by a builder to a company that just focuses on this. Other than sitting down with the client and weighing up all their particular circumstances, it is difficult to recommend a specific importer. Do consider the importer’s track record (how long have they been around, how likely is it they will still be around in 10 years if there’s a warranty claim?), what local support is offered and ask hard questions about who is liable if windows are damaged in transit and how quickly replacements would be provided.

You must factor in a lead time of four to five months for imported windows, starting from the time a deposit is paid. Global pandemics may impact manufacturing and shipping times! Understand your project timeline and if it can accommodate this. Don’t be the person who leaves the builders twiddling their thumbs because the windows haven’t shown up. Consider ordering them well in advance and having them securely stored. This also provides a buffer if there is any damage or other issues.

Third question: performance

Actually, maybe this is the first thing to consider. The building’s predictive thermal performance model (usually done in the PHPP software) can tell you what is acceptable. Then you have numbers and can figure out which suppliers or manufacturers have windows that are suitable.

Even when you understand PHPP and where the numbers go, it’s not always obvious which numbers are most important. Ask the window importer or manufacturer for the window frame and glass properties. If they don’t know what these are, their windows may still be suitable but expect to have to hold their hands to get the data. That will take time and could be a pain in the butt. Your client probably won’t understand how long this will take.

Rules of thumb for Passive House designers (in order of importance):

- Get the glass data for the windows per EN673/EN410.

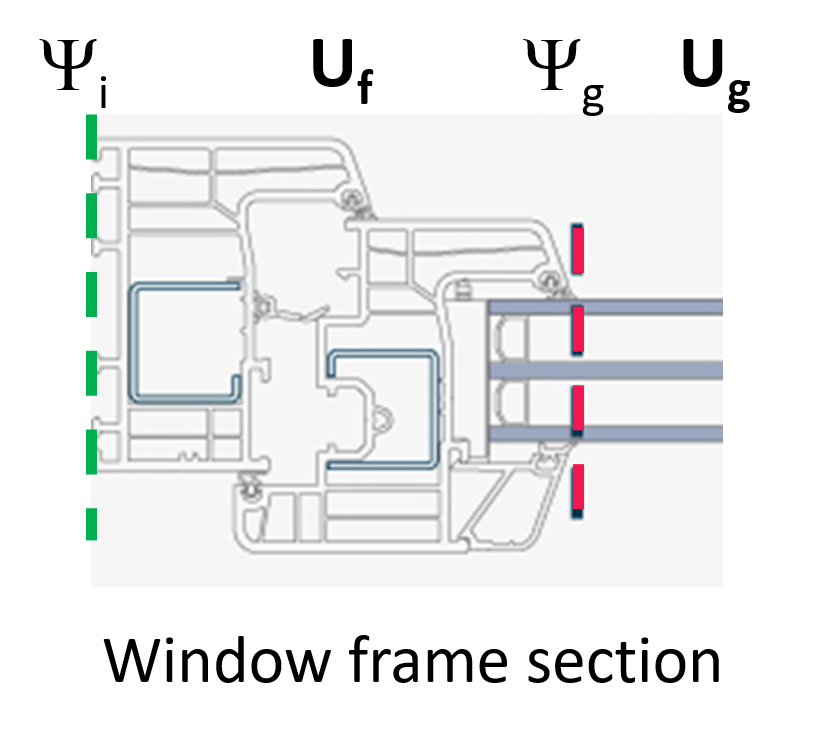

- fRsi is often not available. If not and it’s not obviously okay, this can be an additional cost for the certifier to calculate. Check the frame cross-sections for metal and air spaces with just one seal, lift slide door mullions and sills are especially prone to these thermal bridges.

- Frame size matters a lot. Small windows reduce the ratio of glass to frame; remember the frame usually conducts more heat than the glazing.

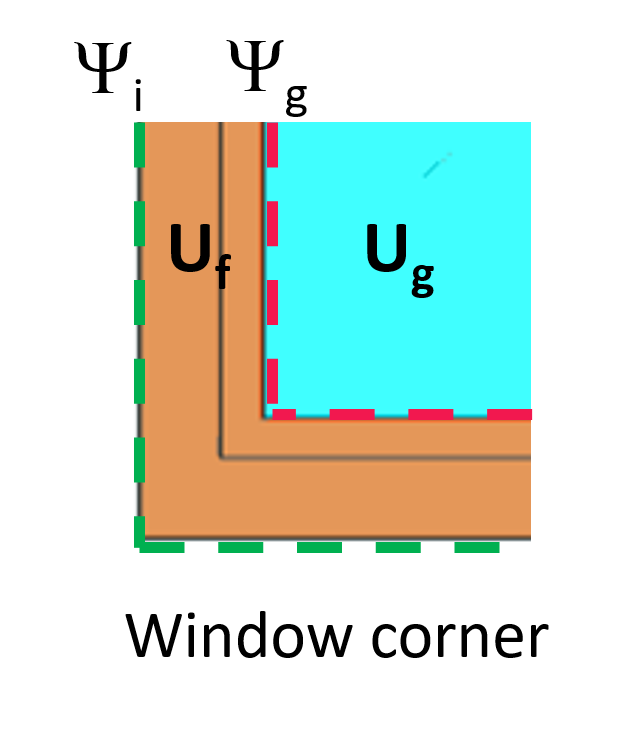

- Uf is important as well as PSI-g for the spacers but make certain the data they provide is for the window frames they are making for you. The data can often be estimated based on similar windows or thickness.

Gotchas

Even if you follow those rules of thumb, here are still some problems that seem to pop up over and over again.

First, make sure the frame can handle the glazing unit thickness that you intend. It’s easy to forget that not every window can handle a 48mm-thick triple-glazed glass unit! The performance for thinner triple glazing can be significantly worse, 50% more energy loss is not uncommon. This is HUGE and can have a horrible impact on overall performance.

The second most common gotcha is extra steel or aluminium in the frame. This is especially common with New Zealand manufactured frames. It strengthens the window but reduces the thermal performance. The best way to catch this is to look for the additional steel or aluminium by comparing the pictures in the thermal performance report to the manufacturer’s frame drawings.

Also common is finding different glass spacers compared to what is used overseas. This is especially common with locally manufactured triple-glazing. The different spaces can significantly impact performance of the windows.

It’s not really a gotcha but don’t forget to allow for different thicknesses of glass. If the window can only handle a certain size triple-glazing unit and thicker glasses is required for strength then the spaces between the glass panes will be reduced and the performance likewise.

Finally, make sure to check the sills and mullions of the frames. Is there is an airspace with only a single seal, or an aluminum insert? Either of these will commonly cause the frame to fail the minimum temperature index or fRSI criteria.

I did say windows were complicated, right?